“Overall, about one-in-five Muslims in Egypt (18%) describe

non-Muslims as not too free or not at all free to practice their

religion. However, Egyptian Muslims are not necessarily troubled by

this perceived lack of religious freedom: Two-thirds of those who say

non-Muslims in Egypt are not too free or not all free to practice

their faith say this is a good thing.” [6]

From Table 5 we can

also see that among respondents who said that people of other

religions were at least somewhat free to practice their religion,

(.05 + .06) / .6248, or 17.6% (roughly), said that this was a bad thing.

Only 4% of

Egyptian Muslims overall said that it is a bad thing that people of

other religions are not too free or not at all free to practice their

religion. If we add that 4% to the 47% who supported the idea of

people of other religions being at least somewhat free, we get about

51% of Egyptian Muslims seemingly supportive of people of other

religions being at least somewhat free to practice their religion.

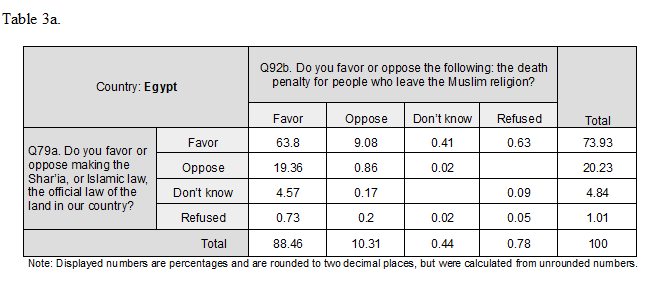

The 2013 Pew Research study at the center of this controversy

reports that 88% of Egyptian Muslims support the death penalty for

people who leave Islam (p. 219, Complete Report). That happens to be

close to what Maher claimed. His critics who claimed that the actual

Pew figure in question was 64% were mistaken. In many cases his critics

were relying on an erroneous secondary source from the popular media

instead of reading the original Pew source with due diligence.

Those who claimed that 75% (or more) of Egyptian Muslims supported

religious freedom seem to have not read or have misread the Pew

(2013) report, which shows that only 24% of Egyptian Muslims overall

responded that people of other religions in their country were very

free to practice their faith and that this was a good thing (p. 173,

Complete Report). Pew used the “very free—good thing” response

combination as its measure of support for religious freedom for

people of other religions (e.g., see p. 63, Complete Report). I also

considered a different measure that included “somewhat free”: At

most, about 47% to 51% of Egyptian Muslims overall supported

religious freedom for people of other religions, assuming that being

at least “somewhat free” is considered an adequate level of

freedom. But when we use opposition to the death penalty for apostasy as our measure,

only about 10% of Egyptian Muslims support religious freedom.

In Part 2, I will examine and present data bearing on the more

general question debated by Maher and his guests in the Oct. 3, 2014

episode of Real Time, namely, what percentage and numbers of Muslims

overall hold fundamentalist views that are contrary to human rights?

I will also explore some possible reasons why some respondents

opposed sharia as the official law of their country but favored some

particularly harsh elements of sharia such the death penalty for

apostasy, stoning for adultery, or corporal punishment such as

whipping and cutting off of hands.

Pew Research is not responsible for my

analyses or interpretation of this data. From the Pew instructions

for downloading data sets: “All manuscripts, articles, books, and

other papers and publications using our data should reference the Pew

Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project as the source

of the data and should acknowledge that the Pew Research Center bears

no responsibility for the interpretations presented or conclusions

reached based on analysis of the data.”

References and Notes

[1] HBO: Real Time with Bill Maher,

Episode 331, October 3, 2014

Maher's guests in that heated

discussion were Ben Affleck, Sam Harris, Nicholas Kristof, and

Michael Steele. [Update: I provide a

transcription of their debate

here.]

[2] Maher's claim, as I heard it, about

8:00 into the above [1] clip: “I can show you a Pew poll of

Egyptians—they are not outliers in the Muslim world—that say like

90% of them believe that death is the appropriate response to leaving

the religion.” Out of context, his use of the term “Egyptians”

is too general, because the study in question reported on the results

for Egyptian Muslims. In context, I believe Maher was referring to

Egyptian Muslims.

Which Pew survey Maher was referring

to is not entirely clear, though “90%” is more consistent with

the 2013 Complete Report, p. 219. *[But see May 17, 2015 update, below]. Maher made a similar statement in

an

interview (posted on Real Clear Politics on September 10, 2014)

on PBS with Charlie Rose, but said “over 80%.” From about 1:22 in

the linked

clip,

Maher tells Rose, “There's a Pew poll of Egypt done a few years

ago. 82% I think it was, said stoning is the appropriate punishment

for adultery. Over 80% thought death was the appropriate punishment

for leaving the Muslim religion.” Maher's phrasing “leaving the

Muslim religion” matches the phrasing used on p. 219 of the (2013)

Complete Report, but also matches the phrasing in the 2010 report (p.

35, and throughout the text, 2010b). For stoning of adulterers,

Maher's mention of “82%” support is matched in the

2010 report (p. 35, 2010b), whereas the 2013 report has 81% for the

sharia-supporting subset (p. 54) and 80% overall (p. 221).

In a more recent interview (December

4, 2014) with Sally Kohn of Vanity Fair, Maher was

quoted,

in response to a question about distinguishing between “radical”

and “moderate” Islam, as follows:

“But as far as

your basic question, this is something that is perhaps not

controversial if you delve into the statistics—and there are

statistics. There’s lots of polling and there’s lots of research

on this subject that connects, lets call them the rank-and-file, with

the extremely illiberal ideas of Islam. Like, if you leave the

religion, it is the appropriate response to have death visited upon

you. That’s not an outlier in the religion. A

Pew poll of Egypt done a few years ago said, I think, 90 percent

of Egyptians felt that if you leave the religion, that’s the

appropriate response.”

The link in the article goes to the

original uncorrected version of Fisher's (May 1, 2013) Washington

Post article, not the Pew (2013) study.

*Update (May 17, 2015). A more recent comment (May 15, 2015), wherein Maher cites other specific numbers for opinions on adultery and apostasy punishments, indicates that he may have derived his "like 90%" from the 86% support for death for apostasy among the sharia-favoring subset data on page 55. It appears that Maher, like many others, thought the subset data were general sample data. I discuss his recent comment

here.

[3] The World’s Muslims: Religion,

Politics and Society, Pew Research Center (April 30, 2013)

I'll call this the Main Report, to

distinguish it from the Complete Report. A key difference between the

two is that the Complete Report contains “Appendix D: Topline,”

whereas the Main Report does not.

(The Main Report's “

Appendix C: Survey Methodology” does contain an explicit reference and link to

“Appendix D,” where it says “The survey questionnaire and a

topline with full results for the 24 countries surveyed in 2011-2012

is included in

Appendix D (PDF).”). Nevertheless, the Overview of the

Main Report tells the reader where to find the full results, and

provides a link. Under the bold heading “About the Report,” it is

stated that “These and other findings are discussed in more detail

in the remainder of this report...The survey questionnaire and a

topline with full results are available as a

PDF,”

and the link is given to the Topline Questionnaire (April 29, 2013),

which has the same material as “Appendix D: Topline” of the

Complete Report, including the Q92b results on p. 219. From the front

Overview page of the Main Report, one can access the Complete Report

and other documents on the right hand side near the top of the page

under the heading “Report Materials.” In the Complete Report on

page 37, under the heading “About the Report,” the Pew authors

tell the reader that “The survey questionnaire and a topline with

full results are available on page 159.”

The (2013) report also includes data

from an earlier Pew study of sub-Saharan African countries, titled

Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan

Africa (April, 2010).

http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2010/04/sub-saharan-africa-full-report.pdf (I cite this study as 2010a)

[5] Topline

Questionnaire. Survey Topline Results. The World’s

Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society. Pew Research Center

(April 29 or 30, 2013).

[6] Neha

Sahgal and Brian Grim (July 2, 2013). Egypt’s

restrictions on religion coincide with lack of religious tolerance.

Pew Research Center, Fact Tank

[7] Pew Research Center Global

Attitudes Project: Muslim Publics Divided on Hamas and Hezbollah

(December 2, 2010)

(I cite this study as 2010b).

[8]

Data

Set (for the 2013 Pew report). The World's Muslims Data Set

(Published June 4, 2014).

Source: Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project.

Retrieved October 19, 2014.

The Pew (2013) Data Set is freely

available upon request within some limits and conditions.

Note that the Data Set folder contains

some pdf files with additional written information about the study,

particularly concerning methodological aspects. Of particular

interest, the quoted instructions for Q92b (apostasy) are from page

37 of 48, in a pdf file titled Pew Research Center Religion and

Public Life Project. The World's Muslims Questionnaire. That file

is one of several that come with the Data Set download.

In addition, I accessed the Data Set

for Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan

Africa (April 15, 2010).

Note that some of these data are

reported in Pew's (2013) report, such as the apostasy data on p. 219.

[9]

For those who wish to analyze and then report results from Pew's data

file, I recommend that only those who have training in statistics and

relevant scientific research methods attempt to do so. Those who

don't have such training should seek to collaborate with and obtain

guidance from those who do. Please see Pew's Instructions

for Downloading Data Sets for more information. That said, the

data file is available for anyone who wants to explore it, within

some limits and conditions [8]. The data can be analyzed using IBM

SPSS, or the open source freely-available (but very basic) PSPP,

or other major statistical packages that can read SPSS .sav files. I

provide instructions for doing a basic analysis of the Pew (2013)

apostasy data here.

[10]

According to Pew: “Data were weighted to account for

differences in probability of selection. Additionally, in some cases

survey results were weighted to match the demographic characteristics

of the population in each country.” Source: Background and

Codebook, Pew Research Center, World’s Muslims Data Set, Survey

Conducted Oct. 2011 – Nov. 2012. This file is one of several

that comes with the Data Set [8] folder.

[11]

Max Fisher (May 1, 2013). 64 percent of Muslims in Egypt

and Pakistan support the death penalty for leaving Islam.

Washington Post. (Original uncorrected version, as viewed December

10, 2014. To switch to the partly corrected version, add a forward

slash to the end of the URL. Note that either version could be

changed).

[12]

Max Fisher (May 2, 2013). What the

Muslim world believes, on everything from alcohol to honor killings,

in 8 maps, 5 charts.

Washington Post. (Uncorrected).

[13] Max Fisher (May 1, 2013).

Majorities of Muslims in Egypt and Pakistan support the death

penalty for leaving Islam. Washington Post. (Partially corrected

version, as viewed December 10, 2014. To go to the uncorrected

version, remove the forward slash from the end of the URL. Article

could be changed).

[14] Christopher Ingraham (October 6,

2014). Ben Affleck and Bill Maher are both wrong about Islamic

fundamentalism. Washington Post. (Subsequently corrected).

[15] Shadi

Hamid. Temptations of Power: Islamists and Illiberal

Democracy in a New Middle East

(2014). New York. Oxford University Press.

(e.g., see p. 57).

(My

transcription).

[18] Some

example usages of “one-in six”:

“In 2012, one in six (15%) adults

exhibited signs of a possible psychiatric disorder...”

“...about one in six use IM (16%) and

video conferencing (15%) applications.”

“Only one in six (16%) describe

themselves as 'old'...”

“...about one in six, or 17.2

percent...”

“About one in six respondents (18%)

would like to reject coal altogether.”

[19] Reza Aslan with Thom

Hartmann (October 20, 2014; posted Oct. 21, 2014). Conversations

w/Great Minds P1: Dr. Reza Aslan - What Do Atheism & Islam Have

in Common? The Big Picture.

Russia Today.

(My transcription).

Also see

this

link if there are problems with the one above.

[20] Laws Criminalizing Apostasy.

Library of Congress. Viewed November 17, 2014.

[21] Among

Pakistani Muslims, 75% said their country's blasphemy laws were

necessary to protect Islam, while only 6% said those laws unfairly

target minorities, about 1% said neither/both equally (VOL), 17% said

they didn't know, and about 1% refused to answer (source: Data Set

[8]; also see p. 199 of the Complete Report, 2013). Pakistan was

apparently the only country wherein the blasphemy question (Q76) was

asked in the Pew (2013) study. An alternative measure of a minimum

level of support for religious freedom in Pakistan would be the

percentage of Muslim respondents there who oppose both the apostasy

death penalty and their country's blasphemy laws, which include the

death penalty and life imprisonment. As the cross-tabulation of Q76

and Q92b in Table 6 shows, only about 1.6% seem to oppose both. That's

assuming that, for these respondents and given the two main explicit

response options (needed to protect Islam vs unfairly target minority

communities), those who say the blasphemy laws “unfairly target

minority communities” (p. 199, Complete Report) show a kind of

opposition to those laws, and hence possible support for religious

freedom.

Appendix I

Would a reasonable reader have known,

or have good reasons to believe—without asking Pew or checking the

numbers in the data file—that the data on p. 219 of Pew's (2013)

Complete Report were of the general samples of Muslims? Here I will

discuss some of the pieces of evidence that suggest that the answer

to that question is 'yes.' The 2013 report is about Muslims' beliefs,

so the default assumption is that when the authors refer to Muslims

of a particular country, explicitly or through contextual or other

implication, and don't mention or imply a subset of Muslims (e.g.,

those who favor sharia), they are referring to the general sample of

Muslims for a country. The researchers tell us in the report when

they are dealing with a subset. For example, on p. 55 of the Complete

Report the results for the subset of Muslims who supported sharia are

shown and described as such. On p. 202, we see that Q81 was asked of

those who favored sharia in response to Q79a. In comparison, in the

table on p. 219, there are no indications that the apostasy question

Q92b was only asked of a subset of Muslims. Likewise, for the sharia

question Q79a on p. 201, there are no indications that it was asked

only of a subset, and p. 46 is clear enough that Q79a was asked of

the general sample of Muslims. Note the consistency of presentation

between Q79a on p. 201 and Q92b on p. 219: neither is preceded by a

note referring to a limit or condition on who should be asked the

question.

Another piece of evidence comes from

the consistency in the presentation of the data in the table for

Q92b, p. 219, of the Complete Report. The table includes data from an

earlier study. These are from the general samples of Muslims in each sub-Saharan African country surveyed. The table includes not only the

2011-2012 data, but also the 2008-2009 data from sub-Saharan African

countries presented in

a

2010 report (2010a). These earlier data are clearly described as

from the general sample of Muslims. On p. 50 (or p. 58 of 331) for

apostasy, “leaving the Muslim religion,” the figure for Q95c is

labeled “Based on Muslims,” as is the table for Q95c on p. 291

(p. 298 of 331) which gives the instructions to the interviewer and

the wording of the question: “ASK IF MUSLIM Q95 And do you favor

or oppose the following? ... c. the death penalty for people who

leave the Muslim religion.” Also see p. 291 (or p. 221 of 254 of

the

Topline, 2010a). The only condition mentioned was that the

respondent be a Muslim. Note that Q95c (2010a) in the sub-Saharan

African study is the same as Q92b for the other countries in the 2013

study.

In the 2013 report, these summaries

for the sub-Saharan African countries are in the same columns as the

more recent data including Egypt, Pakistan, Indonesia, etc. This is a

crucial point. The researchers would not have put the data from these

two different sets in the same columns unless they were all of the

same kind for each country in that table. Otherwise, they would note

the differences. The only difference noted is that the data from the sub-Saharan African countries (except Niger) were collected at an

earlier time (2008-2009) than the 2011-2012 data. Regional

limitations in the survey are noted for Thailand, but the apostasy

question was still asked of all the Muslims who were surveyed within

those regions.

The percentages on page 219 of the

(2013) Complete Report clearly differ overall from the percentages,

for example, on page 55. As one might expect, support for the death

penalty for apostasy tends to be higher among Muslims who support

sharia as the official law of their country. Egypt and Jordan are the

exceptions, where the percentage of support for the death penalty for

apostasy is higher in the general sample than it is among those who

favor official sharia (as described in Q79a). In the case of

Afghanistan, the level (rounded off as reported) is the same between

the general sample and the sharia-supporting subset.

Pew's (2013) results for Muslims

favoring death for apostasy in Egypt (88%), Jordan (83%), and

Pakistan (75%) are consistent with those obtained in an earlier

survey from general samples of Egyptian (84%), Jordanian (86%), and

Pakistani (76%) Muslims (Pew,

2010b).[7]

The Data Set [8] files were made

available to members of the general public for downloading June 4,

2014.* In at least one explanatory pdf document that comes with the

Data Set, the questions are presented with instructions for the

interviewer. For Q92b, the apostasy question, the instructions are as

follows [brackets and parentheses in original]:

“ASK IF MUSLIM

IN ALL COUNTRIES EXCEPT IRAN, MOROCCO AND UZBEKISTAN Q92 Do you favor

or oppose the following? (READ LIST)

a. giving [In

Turkey: Muslim leaders such as Imams, Hodjas and Sheiks; In all other

countries: Muslim leaders and religious judges] the power to decide

family and property disputes [In Russia: In the Muslim Republics of

Russia; In Thailand: In the provinces where the Muslim population

forms a majority]

b. the death

penalty for people who leave the Muslim religion

c. punishments

like whippings and cutting off of hands for crimes like theft and

robbery

d. stoning people

who commit adultery

1 Favor

2 Oppose

8 Don’t know (DO

NOT READ)

9 Refused (DO NOT

READ)”

Pew sources for the above: [8], [10].

The above instructions indicate that

the Q92 set (a, b, c, and d) was asked if the respondent was a

Muslim. Three countries are excluded, and variations on the wording

of Q92a are given for three others, but Q92b pertaining to apostasy

is the same for all Muslims asked. Likewise, for Q92c and Q92d. Aside

from three excluded countries, all Muslims respondents in the

countries listed on p. 219 of the Complete Report, were asked Q92b,

c, and d. There is no condition added where the Q92 set could only be

asked if a respondent had given a specific answer on a previous

question. This means that those who claim the apostasy question was

only asked of those who answered that they favored sharia (answered

favor to Q79a) are wrong.

*Note that while the Data Set and

accompanying files were not directly available to the public until

June of 2014, they were at least available for those who commented on

the Pew (2013) results in response to the Maher-Affleck controversy

in October of 2014.

Appendix II

In response to my request for

verification of my understanding of the apostasy numbers on p. 219 of

the Complete Report (or p. 219 of the Topline Questionnaire, which

has the same numbers), Dr. Bell, the primary researcher of the 2013

Pew study, on October 22 (2014) wrote:

At the request of the author of

Uncertainty Blog I obtained from Dr. Bell permission to quote and photo the

message above, with specific contact information cut out at Dr.

Bell's request.

Appendix III

This section gives a chronological

summary of my attempts to get various sources to correct their

erroneous presentation of Pew's (2013) apostasy numbers. After

October 11 (2014), I became aware that the error had already become

much more widespread than I'd realized initially. On October 15, I

was finally able to address what appeared to be a main source of the

error.

Early May, or

possibly on April 30, 2013. I emailed Sam Harris to correct him re

his tweet of the erroneous “64%” figure for Egypt, and provided

the reference to page 219 of the Pew report.

Result: I don't

know. (No reply to initial email). [Update: Harris cited the correct apostasy number (88%) in a

blog post, September 28, 2015, linking to my brief

guest article version of the above fact-check. In August of 2015, I had emailed Harris with the correction again, after he issued an open

invitation for readers to help him "correct every factual error" he'd ever made. Whether Harris' correct report and link to my guest article resulted from my email, I don't know].

October 9, 2014.

Commented to correct author of Uncertainty Blog re “64%” for

Egypt.

Result: The figure

was corrected, then uncorrected, then later corrected again on about

October 18, 2014.

October 11, 2014.

Notified an editor of Bloomberg View, regarding an article titled

In

Affleck Versus Maher, Everyone Loses (Oct 7, 2014) by

Ramesh

Ponnuru, where the author makes the 64% error for Egypt in

attempting to correct Maher. In my email I cited p. 219 and provided

a link to the Complete Report.

Result: An editor

at Bloomberg View replied the next day, saying he would contact a

director at Pew for clarification. Corrected to 88% sometime shortly

thereafter.

October 15, 2014.

Notified Washington Post re errors on apostasy data in Max Fisher (re

May 1, 2013, and May 2, 2013) articles, and provided Complete Report

link and page 219 reference.

Result: On or

about Oct. 28 or 29, for the Fisher (May 1, 2013) article, they

corrected the apostasy figure for Egypt from 64% to 88%, removed the

red bar plot, introduced new error for Pakistan apostasy figure

(62%), several old errors remain.

October 17, 2014.

Notified

Max

Fisher of his erroneous apostasy numbers,

provided Complete Report link and page 219 reference.

Result: I don't

know. (No reply).

October 18, 2014.

Contacted Primary Researcher of the study in question at Pew for

verification of the apostasy numbers on p. 219 and described problem

with Washington Post article. I cited Egypt as an example.

Result: Received

reply on October 22 confirming that I was correct re the 88% figure

for Egyptian Muslims overall and the data on p. 219 are indeed for

the general samples. (Also see October 29, below).

October 19, 2014.

Obtained the Data Set for the 2013 Pew report, began to analyze it.

Result: Confirmed

the percentages on p. 219 (general sample) and p. 55

(sharia-supporting subset) of the Pew (2013) report.

October 27, 2014.

Notified the Washington Post regarding their errors for Pew's

apostasy and adultery data in article by Christopher Ingraham (Oct.

6, 2014), provided link to Complete Report and pp. 219 and 221. I

told them that I'd confirmed with Pew.

Result: Correction

was made subsequently, though I don't know when exactly, or whether

this was related to my notification to them. (Checked December 10,

2014).

October 27, 2014.

Notified Christopher Ingraham of his error, provided in email message

history the same information given in my notification to the

Washington Post.

Result: No reply,

but see above. Correction made.

October 29-31,

2014. Re Fisher, May 1 2013 article, apostasy data. Notified the

Washington Post expressing appreciation for their correction of the

figure for Egypt, but also informing them of their new error for

Pakistan, and the other errors that remained in the text of the

article.

Result: Except for

the 88% for Egyptian Muslims, several errors remain. I had a brief

exchange via email with an editor, in which I again cited p. 219 of

Pew's 2013 Complete Report and told them I'd confirmed with Pew, but

this was to no avail. Not fully corrected as of January 20, 2015.

December 1, 2014.

Notified Washington Post of the erroneous claim that “more than

75%” of Egyptian Muslims supported religious freedom in the Fisher

(May 1, 2013) article; provided link to Complete Report, page

references, and explanation.

Result: Not

corrected as of January 20, 2015.

Appendix IV

Here is a small non-scientific

sampling of writers who mistakenly spread the 64% error, or other

errors related to apostasy or religious freedom or the Pew data. If

one searches in a web browser the key word combinations such as

“Egypt,” “64%,” “Muslims,” “leaving Islam,” etc., a

very large number of examples come up. Some examples link to or cite

the original Washington Post (May 1, 2013) article, while others

don't. Some tried to correct Maher by using the 64% figure, with or

without reference to the Washington Post (May 1, 2013) article. I

checked these sources again on December 12, 2014, or later. Note that

any of these examples may be changed later by their authors or

editors. I've categorized the errors. [I invite any of the authors listed below who've subsequently corrected their numbers to please notify me and I will note the corrections here].

1. Persuaded, by people purporting to

correct them, into relaying incorrect apostasy figure(s).

Sam Harris,

tweet,

April 30, 2013, 7:03 pm. Note that this 64% error occurred before the

WP article. [In an article on September 15, 2015, Harris cited correct figures by

linking to my guest article fact check at Uncertainty Blog].

2. Relayed the incorrect apostasy

numbers directly or indirectly from the Washington Post.

Daniel Dennett,

Facebook

post, May 1, 2013, from a

GSHM

(Global Secular Humanist Movement) citation of Fisher's Washington

Post article, May 1, 2013.

Allahpundit,

Hot

Air article, May 1, 2013. (Also includes the false claim that in

the Pew (2013) study “Only those Muslims who first said that they

support sharia law were asked whether apostates should be executed”).

"In Egypt and

Pakistan, 64 percent support executing for apostasy.” Source cited

is the WP article by Max Fisher (May 1, 2013).

Ali A. Rizvi,

blog

article, Huffington Post, October 6, 2014.

For the apostasy

data, Rizvi includes a correct link to the Pew (2013) Complete

Report, but also a link to the Washington Post (May 1, 2013) article.

On January 16, 2015, in an article for CNN, Rizvi

quoted

the partially corrected Washington Post (May 1, 2013) Fisher article,

incorrectly claiming that the Pew (2013) study showed that 62% of

Pakistani Muslims support death for apostasy.

Razib Khan,

blog

post, Gene Expression Blog, October 7, 2014.

Used the

Washington Post's incorrect apostasy numbers from the original

uncorrected Christopher Ingraham (October 6, 2014) Washington Post

article. Khan discussed the Affleck vs. Maher/Harris incident and

tried to get an estimate of the numbers and percentages of Muslims

overall who supported death for apostasy.

Richard Dawkins,

retweet,

October 9, 2014.

Where Maher is

quoted referring to the “Pew poll” that he claims showed “90

percent of Egyptians” support the death penalty for apostasy, a

link to the original uncorrected Washington Post (May 1, 2013)

article is inserted instead of a link to the Pew study.

Years later, the errors continue...

PragerU,

video, "Where are the Moderate Muslims?" April 27, 2017.

At 1:44, the narrator says that according to Pew "62%" of Pakistani Muslims favored the death penalty for apostasy. The error appears to be based on the above-noted Washington Post attempted correction of their May 1, 2013 article.

Apostate Prophet,

video, "The Death Penalty for Leaving Islam," July 12, 2019.

The narrator cites Pew and says that, among Muslims who think Islam should be the law of the state, 6 of 10 Pakistani Muslims (1:47) support the death penalty for apostasy. This error appears to be based, again, on the erroneous Washington Post (May 1, 2013) article or the attempted correction of it.

3. Attempted to correct Maher by using

[or while citing] the Fisher WP (May 1, 2013) article, misrepresented Pew data.

Omar Baddar,

article,

Huffington Post, May 13, 2014.

In response to

Maher's comments made in the spring of 2014 mentioning the Pew

apostasy figures for Egypt, Baddar linked to the Washington Post (May

1, 2013) article and

wrote:

“Bill Maher attempted to cite an Egypt poll, saying it showed that

80-90% of people in the country approved of death as a punishment for

leaving Islam. The

actual

number is 64%, which is still horrifyingly high, and I am alarmed

by it.”

Rossalyn Warren,

article,

Buzzfeed, October 6, 2014.

Tries to correct

Maher's statement (from Oct. 3, 2014) by citing the Washington Post

(May 1, 2013) article: “In fact, the poll he is referring to states

that in both Egypt and Pakistan

64%

hold this view, not 90%.”

Cenk Uygur,

video

presentation/talk, The Young Turks, published October 6, 2014.

Uygur responds to

Maher's and Harris' (October 3, 2014, HBO: Real Time with Bill

Maher) citation of polls. In a section beginning at about 10:52

in the clip, Uygur makes the usual mistake of confusing the Pew data

with the erroneous Washington Post/ Fisher numbers. Uygur said

“This,” while looking at a paper and setting up for displaying

the red bar plot, “comes from Pew Research Center,” and the

“Washington Post wrote an article about it.” But he doesn't tell

viewers that the numbers, the red bar plot, and the descriptive title

of the red bar plot that he shows and reads from to counter Maher come

from Fisher's Washington Post (May 1, 2013) article.

When Fisher's red bar plot is on the screen from approximately 11:04

to 11:50, Uygur is talking about the numbers, and the source for the

plot is labeled falsely by The Young Turks as “Pew Research

Center.” Fisher's labeling of the source as “Pew” is also

visible at the bottom of the plot.

10:52 Uygur [my

brackets]: “Now there are polls that are really troubling, which

they mention later. And here, let me show you one. Okay. And this

[10:58, touching a paper] comes from Pew Research Center. Washington

Post wrote an article about it. Share of Muslims who support the

death penalty for leaving Islam. [11:04, the red bar plot is first

shown on the screen] Okay. Now, when you look at some of the

countries down at the bottom there or at the top, however you want to

look at it, Afghanistan's over 60%, Pakistan is right around 60% as

well, Egypt—uh, so those are really really troubling. When you look

at the other end though, almost no one in Kazakhstan thinks that, or

Albania, or Turkey, or Kosovo, and the list goes on and on.”[11:25]

13:30 Uygur says

of Indonesian Muslims that “a disturbing number, a little over 10%

say that apostates should be executed,” while, he says, “closer

to 90%” of them say people “should not” be killed for apostasy.

According to Pew (2013), 16% favored and 77% opposed the penalty, see

p. 219.

15:34 Uygur

comments directly on Maher's “90%” figure for Egypt: “And as we

just showed you the numbers he's referring to, he actually got it

wrong, it's actually a little over 60% of Egyptians believe that,

which is still a very disturbing number, but it's not 90%.” Uygur

attempts to use the Washington Post/ Fisher numbers to correct

Maher's claim about Pew's numbers.

Nida Khan,

article,

Huffington Post, October 14, 2014.

Responding to

Maher's recent Islam controversy, Khan

wrote

that his “90%” figure was wrong, and that the “actual figure

was 64%.” She linked to the Pew (April 30, 2013) study, but cited

and relayed some of the Washington Post's (May 1, 2013) erroneous

apostasy and religious freedom numbers.

John Sexton,

blog

article, Breitbart, October 14, 2014. [Update: See John Sexton's note Feb. 21, 2015,

here]

Refers, cites, and

links to Fisher's (May 1, 2013) Washington Post article, and links to

Pew's (2013) Complete Report, but proceeds to make the same error as

Fisher, and says that Maher's claims about Pew's apostasy numbers for

Egypt (variously, “90%” or “over 80%”) are wrong.

4. Attempted to

correct Maher with 64% figure, but didn't mention the WP (May 1,

2013) article.

Ramesh Ponnuru,

article,

iPolitics, October 8, 2014. (Published in many venues).

Ponnuru

cites and links to the Pew (2013) study, but uses the 64% apostasy

number for Egypt to correct Maher: “Maher overstated his point: It

isn’t true, as he asserted, that 90 per cent of Egyptians support

the death penalty for leaving Islam. But the true number—64 per

cent according to a Pew

Research Center

poll—is bad enough.” Ponnuru also cited the Ingraham

Washington Post (October 6, 2014) article earlier in the piece.

Waleed S. Ahmed,

article,

Muslim Matters, October 9, 2014.

To refute Maher,

Ahmed includes a link to the Pew (2013) Complete Report. He falsely

claims that the Pew report “...offers no direct statistics on

Muslims who support capital punishment for apostasy.” He apparently

did not read p. 219 of the report to which he linked. He writes

regarding those “direct statistics” that “...even

if they were to be extrapolated (which introduces an error), the

support would be at 64% – not the 90% he so forcefully claimed.

Maher also fails to mention the significant disparity Egypt has with

other Muslim majority countries on this issue: Indonesia (13%),

Lebanon (13%), Tunisia (16%) and Turkey (2%).” (parentheses in

original).

Ahmed doesn't cite the Fisher (May 1, 2013) article, but it is

interesting to note the similar phrasing.

Ahmed

Benchemsi, article,

Salon, October 13, 2014.

Benchemsi claimed that the Pew (2013) survey was unreliable. He

alleged that respondents were not free to give honest answers due to

fear of repercussions. In attempting to correct Maher's “90%”

claim, he linked to Chapter 1 of the Pew (2013) report. He apparently

used the 86% and 74% figures from Chapter 1 to obtain 64% in order to

“correct” Maher. He also linked to the Topline Questionnaire pdf

and cited it in an attempt to support a different allegation against

the researchers, but apparently didn't reach p. 219 that has the

apostasy data.

Omar Sarwar,

article,

Huffington Post, November 6, 2014.

Sarwar linked to

Pew's (2013) Complete Report when he wrote: “While jousting with

Affleck, Maher

cited

the Pew Research Center's 2013

The World's Muslims report,

declaring that 90% of Egyptians believe that apostasy should be

punishable by death. In fact, the report shows that 64% of Egypt's

Muslims hold this view.” [Update: Sarwar's article contains a correction with the 88% figure. The correction was made some time after February 21, 2015]

5. Attempted to support Maher using

erroneous apostasy figures from the Washington Post.

Dustin Siggins,

article,

Daily Caller, October 8, 2014

Siggins cited the

Pew (2013) survey and the then-uncorrected Washington Post article by

Ingraham (October 6, 2014) for erroneous apostasy figures, and even

quoted some of them incorrectly from Ingraham.

6. Erroneous 64% figure is given, but

no source is mentioned.

Kashif

Chaudhry, blog

article, The Express Tribune, October 17, 2014.

Chaudary doesn't directly accuse Maher of having the wrong numbers.

He cites the 64% figure for Egyptian Muslims and a couple of other

figures that are consistent with the Washington Post's (May 1, 2013)

apostasy numbers but provides in the article no mention of or direct

references to sources for them.

7. False claim made

that only Muslims who favored official sharia were asked the apostasy

question.

Wikipedia,

article on apostasy, as it appeared January 19, 2015.

Note that

Wikipedia refers to the Pew (2013) report as the “2012 Pew Survey,”

and links to the Main Report, which opens to show Chapter 1 and on

the right hand side the “Report materials” including the Complete

Report and the Topline Questionnaire, which they apparently ignored.

“

The support for a death penalty

among all Muslims in those countries is unclear from 2012 Pew

survey,[115]

which surveyed support for death penalty only among those Muslims who

favor Sharia as the official law of the land. The exact percentage is

also unclear from this survey, as it does not include Muslims who may

favor a death penalty for apostasy yet do not favor Sharia as law of

the land.”

[Update, February 13, 2017. After a comment by a reader, I noticed that Wikipedia has removed their explicit claim that only those who favored sharia were asked the apostasy question, but their description and presentation still makes no mention of the general sample data on page 219 of Pew's full report. They still extrapolate the apostasy numbers (see "Group C") incorrectly, apparently based on Pew's reported sharia-favoring subset apostasy data, though they at least admit that those extrapolated numbers are theirs and not Pew's.]

8. Erroneous description of Pew's

religious freedom data.

Dan Merica,

blog

article, CNN Religion Blogs, April 30, 2013.

Merica mistakes

the percentage of a subset of Muslims for the percentage of Muslims

overall:

“Despite

views that Islam should influence politics and law, an overwhelming

number of Muslims told Pew that religious freedom was a good thing.

Ninety-seven

percent of Muslims in South Asia, 95% in Eastern Europe, 94% in

sub-Saharan Africa and 85% in the Middle East and North Africa

responded positively to religious freedom, according to the poll.”

The numbers Merica cites come from the Overview of Pew's (2013) report (e.g., see Complete Report, p. 32). However, Pew describes those results as taken from a subset of Muslims:

“The survey also

asked Muslims whether people of other faiths in their country are

very free, somewhat free, not too free or not at all free to practice

their religion; a follow-up question asked Muslims whether they

consider this “a good thing” or “a bad thing.” In 31 of the

38 countries where the question was asked, majorities of Muslims say

people of other faiths can practice their religion very freely. (The

question was not asked in Afghanistan.) And of those who share this

assessment, overwhelming majorities consider it a good thing.” (p.

32)

The

medians for Muslims overall can be obtained from the “very

free—good thing” column on p. 173, as follows: South Asia 66%,

Eastern Europe 70.5%, Sub-Saharan Africa 74.5%, and Middle East North

Africa 47%. (For the two regions Merica didn't mention, SE Asia and

Central Asia, the medians were 50% and 48%, respectively, see p.

173).

Economist.com,

article,

April 30, 2013.

Contains the

following: “CORRECTION: The original version of this post misread a

footnote in Pew's fine study. The first chart and the text were

changed to reflect this on May 3rd.”

Although the

Economist's correction didn't describe that error explicitly,

another

article that reproduced what could be the Economist's original

uncorrected first chart indicates that the error involved the

confusion of results for a subset with overall results for Muslims on

religious freedom.

9. In the wake of the Oct. 3, 2014

episode of Real Time, broad unsubstantiated allegation that

Maher's factual or statistical claims are false or fabricated.

Aymen Mohyeldin,

interview

remarks, with Lawrence O'Donnell, MSNBC, October 8, 2014.

(0:47) “...they

[Maher and Harris] skewed numbers, they made up numbers that we

weren't really sure where they came from, they didn't really

substantiate them with uh, you know, credible sources of

journalists...”

In fact, Maher at

least referenced Pew on his apostasy number for Egypt. On May 14,

2014, Mohyeldin

cited

Omar Baddar's article (see above) as a refutation of Maher's comments

about Islam in May, 2014 (Baddar made the 64% error for Egypt in

attempting to correct Maher by using Max Fisher's erroneous May 1,

2013 article). On October 6, 2014, Mohyeldin

linked

to the Pew (2013) survey in an apparent attempt to support his broad

accusation that Maher's and Harris's “misinformed” claims were

“not based on fact.” Though he provided a link to the Pew (2013)

source, he didn't show that any factual or statistical claims made by

Maher or Harris were false.

10. Miscellaneous/General: False claims, recklessness, and/or conceptual confusion among influential people reporting the Pew apostasy numbers in various media.

[Update, added November 1, 2015] On April 30, 2013, Jeffrey Goldberg misread a secondary source (The Economist) presentation, mistaking the sharia subset for the general sample results, and tweeted it. In claiming that "almost 90%" of Egyptian Muslims favored death for apostasy, Goldberg happened to be consistent with Pew's report, because both 86% (subset) and 88% (general) are almost 90%. Glenn Greenwald, who was also apparently unaware of the primary source figures, then tried to correct Goldberg's misreading of the secondary source, but added a slightly inaccurate number ("72%") for the percentage of "Egyptians" who "believe in sharia law." Goldberg then tweeted a "corrected" (but false) claim that "Roughly 65 percent of Egyptian Muslims support death for apostasy." Goldberg and Greenwald were apparently unconcerned with consulting the primary source report for the correct general sample figures for Egyptian Muslims on the apostasy question.

Appendix V

With regard to

Aslan's comment about the “massive” diversity of meanings of

sharia among Egyptian Muslims who supported sharia, the Pew (2013)

report does not give the results for that subset on most of the

questions related to marriage, divorce, and inheritance laws under

sharia, or about sharia generally, but they do provide results for

the general sample's personal or moral opinions on these issues. I

will summarize some relevant results for Egyptian Muslims as follows

(page numbers are from the Complete Report):

70% were not

too/not at all comfortable with the idea of their son marrying a

Christian (p.186);

93% were not at all comfortable with the idea of their daughter

marrying a Christian (p. 187);

95% said sex between people who are not married to each other is

immoral (p. 212);

41% said polygamy was morally acceptable (vs. 43% in the

sharia-supporting group, see p. 87), 8% said it was morally wrong,

35% said it was not a moral issue, and 16% said its acceptability

depended on the situation (p. 205);

56% said divorce was morally acceptable, 6% said it was morally

wrong, 26% said it was not a moral issue, 12% said it depends on the

situation (p. 204);

73% said a wife should not have the right to divorce her husband (p.

199);

85% completely or mostly agreed that a wife must always obey her

husband (p. 93);

65% said sons should have greater inheritance rights, 6% said

daughters should have greater inheritance rights, 26% said both

should have equal rights (p. 203).

75% said sharia is the revealed word of God, 20% said it is developed

by men based on the word of God (p. 194).

18% said the laws of the country follow sharia very closely, 21% said

somewhat closely, 39% not too closely, 17% not at all closely, and 6%

dk/ref. (p. 195).

The above list of

results overall seems to show at least as much unity as diversity.

Aslan's diversity claim happens to be consistent with my last listed

item showing a wide divergence of opinion on how closely the laws of

the country follow sharia (Q68), though this was reported for the

general sample, not the 74% subset to which Aslan referred.

(According to my analysis of the data file, there is a wide

divergence of opinion among Egyptian Muslims on Q68, whether they

favor or oppose sharia). The results for Q67, which asks whether

sharia law has one true interpretation or should be open to multiple

interpretations, weren't available for Egypt due to “an

administrative error” (p. 195). Having presented that summary, I

will leave it to the reader to interpret Aslan's response to Hayes'

question.

_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*

Honoring your request to move discussion from Twitter, Pew Research laid the foundation for the misunderstanding of its report. The report supposedly addresses the attitudes of Muslims, yet in the section of the report dealing with attitudes toward apply the death penalty for apostasy, all the data refer to the subpopulation of Muslims who favor sharia. Sure, page 219 has the data for Muslims in general, but where's that information in the body of the report? If one used a search for "apostasy" on the PDF (like I did), they'll only find data applying to the aforementioned subpopulation. The report effectively buries the information you (rightly) point out on Page 219.

ReplyDeleteHi Bryan. This is much easier. I just started using twitter recently.

DeleteI agree that Pew should have presented the general stats up front, before the subset data. I do think that contributed partly to a lot of people misunderstanding the subset info. I think Pew underestimated the potential for misunderstanding on this one. (In previous reports, they presented general figures [up front] for the apostasy and adultery questions, for example). That said, as I mention in note [3] in my article above, Pew mentions where to find the "questionnaire and a topline with full results," and the Topline pdf is the same as what's in Appendix D of the Complete Report.

For searching, p. 55 in the Complete Report gives the question number Q92b, and searching that takes you to p. 219. There is of course no p. 219 in the web version, but again, the web version at least gives the link to the Topline pdf (which does have p. 219), and in any case the Complete Report pdf is available from the top of the opening page of the web version.

A key issue is how much of the misunderstanding is due to Pew's presentation, and how much is due to readers rushing through too quick and not being careful enough about what they then conclude and report. For those who extrapolated numbers to end up with numbers the same or similar to what Fisher presented, I think it's clear that not enough questions were answered or explored in their preparation process, given everything that Pew provided. One needs to know the wording of the question, the percentages who opposed, didn't know, etc. If you look for that info in what Pew provided, you should find it. If you don't find it, you can contact them to find out.

It also helps to look at previous reports by Pew on this subject. The previous reports have a similar layout, with the general results in the back or in an appendix with "Topline" results.

I think there is also a greater burden of responsibility on writers to do a much more thorough and active read than, say, a casual reader who's just browsing a few areas of interest. If you're writing about it, there's a greater responsibility. So I would [place more responsibility on] those who wrote articles about the report (or discussed it on television to potentially hundreds of thousands of viewers) more than I would those who were only discussing it casually. But I focussed in my discussion in the above document on those who not only got the numbers wrong, but especially on at least two of the journalists and one scholar (Aslan) who are supposed to be knowledgeable about this area, and who--remarkably--persisted with the error (or didn't acknowledge or correct it fully) despite being warned and corrected at least once. Most of the other cases I list in Appendix IV were not as bad, though the Nida Khan and Cenk Uygur errors were pretty bad.

In any case, kudos to you for acknowledging the error.

I don't disagree with anything in your reply. Nor does it look like you disagree with anything I posted here.

DeleteI take responsibility for my error in not finding the information on the general Muslim opinion on apostasy, but at the same time it's fair (as you appear to agree) to point out how Pew made the error easy to commit. Any stated reference in the report to the attitudes of Muslims generally to the death penalty for apostasy would have cued readers to the existence and importance of Q92b.

Hmm. I wouldn't say they made the error "easy to commit."

DeleteThey didn't make their report 100% optimally clear and fool-proof, but that's not the same as making it easy for errors to be committed. I think Pew exercised at least adequate diligence in presenting the information. I think, as far as survey reports go, this one is pretty clear and reader-friendly. It wouldn't be fair to fault Pew for an (arguable) imperfection, while attributing equal blame to some reporters for not exercising basic due diligence in their presentation of Pew's work. Those who reported erroneously, and/or reported erroneous extrapolations, etc., are much more to blame.

Pew provided all the information any reader exercising adequate diligence would need to get a correct understanding of the apostasy data. If you're writing about the Pew report, you can't reasonably ignore something called the "Complete Report." In that Complete report, you can't reasonably ignore Appendix D, a section which constitutes roughly 30% of the pages in the document.

Pew is not responsible for the erroneous extrapolation that people used. People either came up with that erroneous extrapolation themselves independently, or they got the idea from other secondary sources. (Or there could be a combination of the two. For example, they came up with an extrapolation, noted that others had obtained the same results, and took that agreement as a kind of validation). Either way, the error is not from Pew.

"Pew provided all the information any reader exercising adequate diligence would need to get a correct understanding of the apostasy data."

DeleteIf you mean adequate for obtaining a correct understanding of the apostasy data, yeah. But that's a tautology. A person going to the apostasy section of a report on Muslim attitudes will encounter only data for the subset of Muslims who favor sharia, and will find no mention of the apostasy attitudes of the general Muslim population on the subject.

I don't see that omission as easy to defend in a report supposedly addressing the attitudes of Muslims. Either Pew should have provided an explanation for its focus on the subpopulation in that section, or else provided some other cue to readers that it collected data on general population (like "See Appendix D for data on the general Muslim population"). Or both. Lacking any of those, it counts as an oversight in the preparation of the report.

As you say, no communication is foolproof. But this omission is fairly glaring.

Bryan,

Delete"A person going to the apostasy section of a report on Muslim attitudes will encounter only data for the subset of Muslims who favor sharia, and will find no mention of the apostasy attitudes of the general Muslim population on the subject."

On the opening web page, you've got the Complete Report, and the Topline Questionnaire, and within the opening page text a reference to the "full results" with a link to the Topline Q. pdf. You can't miss it if you read the report. If you peruse the Topline, you'll eventually find Q92b. In the Complete Report, Appendix D: Topline is listed in the Table of Contents. From the Complete Report, p. 37: "The survey questionnaire and a topline with full results are available on page 159." In other words, if you read p. 37, then read along further, come to p. 55 that shows subset results, and have some questions about the full results, you know where to find them: Appendix D: Topline.

"I don't see that omission as easy to defend in a report supposedly addressing the attitudes of Muslims."

I wouldn't say it's an "omission," at least not by Pew. You can't ignore an entire section, 30% of the Complete Report, and then blame Pew for what you omitted in your reading. The way these reports are presented, there's a Topline with full results in the back.

But even if Pew had only presented subset data and no general sample data anywhere in the report or report materials, that still doesn't justify some people making erroneous extrapolations. If some people thought they were stuck with only being able to report subset data and didn't want to investigate further, then they should have just reported the subset data. They shouldn't have ventured into extrapolations based on inadequate information.

"Either Pew should have provided an explanation for its focus on the subpopulation in that section, or else provided some other cue to readers that it collected data on general population (like "See Appendix D for data on the general Muslim population"). Or both. Lacking any of those, it counts as an oversight in the preparation of the report."

I don't think it's an oversight. Q92b is a cue on p. 55. For one thing, you need to know the wording of the question. That's provided in the Topline/Appendix D. You need to know what percentage opposed, didn't know, etc. Searching for Q92b will take you to p. 219. Also, scrolling through past p. 159 will take you to the full results for all of the questions in the report, including Q92b on p. 219.

As I said before, their presentation is not optimal. I believe that general data should be presented before subset data, but that's not a sufficient excuse for people not reading the whole report or not looking for all the relevant information. And it's not an excuse for the errors that some people produced.

What I think Pew should have done, after the error became widespread, was publish a corrective article explaining the error. That way people would have an authoritative correction. Pew has obviously invested a lot in this research, so they do have a strong interest in ensuring, as much as they can, that the public has a correct understanding of the data.

"On the opening web page, you've got the Complete Report, and the Topline Questionnaire, and within the opening page text a reference to the "full results" with a link to the Topline Q. pdf. You can't miss it if you read the report."

DeleteIf you're not saying that reading the whole report will cause one to eventually read something that's in the whole report, I'd like for you to clarify what it is you're saying.

"If you peruse the Topline, you'll eventually find Q92b."

In the Topline, there's is no information regarding what subpopulations were asked the questions. As such the Topline document offers no clarification of the subpopulation issue created by the ambiguity in section of the report addressing punishment for apostasy. It's one thing for a report to fail to guarantee understanding. It's another thing to put important information in out-of-the-way places while omitting cues to the reader to look for that specific information. It's a stretch to call Q92b a cue. Nobody's going to read "Q92b" and think "A-ha, that's where to look for the results of the apostasy question as posed to the general Muslim population!" That's about as vague as a cue can get. And going to Q92b doesn't inform the reader that the question was addressed to the general Muslim population, either. One would have to notice a discrepancy in the numbers and either assume the discrepancy stems from addressing 92b to the general Muslim population or ... ask the authors. If asking the authors is necessary then the report isn't clear on its own.

"I wouldn't say it's an "omission," at least not by Pew. You can't ignore an entire section, 30% of the Complete Report, and then blame Pew for what you omitted in your reading."

Kindly point me to any part of the report that clearly states Q92b was addressed to the general Muslim population.

Meanwhile, we've got stuff like this from the section on favoring Sharia as the law of the land:

"By contrast, fewer Muslims back severe criminal punishments in Southeast Asia (median of 46%)"

That 46 percent matches the figure on the adjacent chart, which is described as applying to those Muslims who favor sharia. Very shortly after that, the introductory page invites the curious to find out more about views on apostasy in the main report (which, as previously noted, presents *only* information about Muslims who favor sharia). Follow that link to find out more about Muslim views about sharia and you won't find out about the general Muslim view without looking up Q92b and assuming it was asked of Muslims generally (going by the report contents and Topline document).

If I did that I'd admit it was a mistake.

"that's not a sufficient excuse for people not reading the whole report or not looking for all the relevant information."

You don't need to convince me on that point.

Bryan, (part 1 of 2)

DeleteFirst of all, thanks for making the correction on your site.

"In the Topline, there's is no information regarding what subpopulations were asked the questions. As such the Topline document offers no clarification of the subpopulation issue created by the ambiguity in section of the report addressing punishment for apostasy."

The wording of the questions (and/or some instructions to the interviewer) in the Topline does contain information about what population or subpopulation was asked. As I pointed out in Appendix I, above, the wording for Q81 for example indicates that it was asked only of those who favored sharia. I'll quote it here: "ASK IF RESPONDENT SAYS FAVOR IN Q79a (Q79a = 1). Q81. Should both Muslims and non-Muslims in our country be subject to sharia law, or should sharia law only be applied to Muslims"

In contrast, the wording of Q79a has no specification of a subgroup. We know or have strong reasons to believe from the report (e.g., p. 46 of the Complete Report, also see the same section in the Main Report) that Q79a was asked of Muslims generally. If you look all through the Topline, you'll see most questions have a general wording, with no conditional (subset) specification, whereas a smaller number of them do have a specification. (Another that has a subset specification is Q11, which I quote in my article). Q92b is the same as Q79a in that there is no specification of a subset. No specification of a subset means it's of the general sample of Muslims.

The second piece of evidence in the Topline section occurs in the tables, and at the bottom of the tables. As I noted in Appendix I, the sub-Saharan African countries (except Niger) in the table for Q92b were surveyed in 2008-2009, and the note at the bottom of that table refers to that (2010) report. When you go to that report, you find that the apostasy question (same question but with a different number code) was asked of Muslims generally and the results were reported for Muslims generally. The fact that those results on p. 219 of the 2013 report are in the same columns as the data collected later (2011-2012) from other countries indicates that they are all for the general samples. Any differences would have been noted on p. 219 (2013). The only difference noted there, aside from the regional limitation for Thailand, is that the data for the countries with an asterisk were obtained at a different time and reported previously.

As you yourself noted earlier, and as I noted in Appendix I, the (2013) report is clearly about the opinions of Muslims. If the report doesn't specify or imply a subset of Muslims, then the default assumption is that it's referring to the general sample of Muslims.

(part 2 of 2)

Delete"...the Topline document offers no clarification of the subpopulation issue created by the ambiguity in section of the report addressing punishment for apostasy."

The sharia section of the text of the report addresses apostasy (p. 55) among other issues. The section is about Muslims' beliefs about sharia, the apostasy data are presented in that context, and what's presented there is described clearly as of the sharia-supporting subset. That's not ambiguous. It's a subset. It can be contrasted and compared with the p. 219 data.

“It's another thing to put important information in out-of-the-way places”

The Complete Report and Topline Questionnaire are not in “out-of-the-way places.” They are there for the reader at the top right of the screen when you open up the web page version of the report. Also, the first page of the web page overview tells you the “full results” are in a pdf for which it provides the link.

Second, the Complete Report has a Table of Contents. It is a pdf. It is searchable.

Third, more is expected of the writer than of the casual reader. "Out-of-the-way places," even if it were true, isn't a valid excuse for a writer, who is expected to find and understand all relevant aspects of the report.

“while omitting cues to the reader to look for that specific information.”

If readers think they don't have the information they are looking for, they should try to find it. “Full results,” “Complete Report,” “Topline Questionnaire,” “Q92b” are cues, clues, indications for those who are seeking more information.

“It's a stretch to call Q92b a cue. Nobody's going to read "Q92b" and think "A-ha, that's where to look for the results of the apostasy question as posed to the general Muslim population!" That's about as vague as a cue can get.”

It's the exact number of the question you are looking for if you are seeking to find important additional information, including whether the question was asked of the general population, its exact wording, what percentages opposed, didn't know, etc. They number the question and cite it in the report so that you can look it up and find additional information about it. If you search it in the Complete Report or the Topline Questionnaire, you'll find it. The main report web page tells you where to find the full results and gives the link to the Topline Q. with those full results.

“And going to Q92b doesn't inform the reader that the question was addressed to the general Muslim population, either.”

As I noted above, and in Appendix I, the question is worded without any specification of a subset, in the context of the Topline which does have some other questions that, by contrast, do specify a subset.

“One would have to notice a discrepancy in the numbers and either assume the discrepancy stems from addressing 92b to the general Muslim population”

The discrepancy in the numbers (p. 55 vs p. 219) is obvious. The idea that the difference stems from p. 219 being from the general sample fits with the fact that the wording of the question is general, and from the other information I mentioned.

“or ... ask the authors. If asking the authors is necessary then the report isn't clear on its own.”

For some issues, in any area of research, it is necessary to contact the researchers for more information. It's not unusual for journalists who are writing about scientific research to contact the researchers/authors for clarification on some issues. There is a much greater responsibility on writers to obtain verification, even if an interpretation seems to make sense. In this case, though, my view as expressed in Appendix I is that the diligent reader has enough resources available online in the 2013 and 2010 reports from Pew to determine that p. 219 refers to the general sample.

"First of all, thanks for making the correction on your site."

ReplyDeleteNo thanks necessary, though it's appreciated. I have the "Report and Error" icon featured on the site for a reason. I'm serious about getting things right, even if it takes more than one try.

While I appreciate the depth and length of your reply, only select parts of it interest me in terms of my response. This will be my last word on the subject unless you surprise me with something you haven't already expressed.

"The wording of the questions (and/or some instructions to the interviewer) in the Topline does contain information about what population or subpopulation was asked."

Not with respect to the apostasy issue. As you note later, one gleans the information about the population involved in Q92b by using a default *assumption*. That assumption is only a strong assumption based on a nearly complete reading of the report. I say the report should be written clearly enough so that one does not need to read nearly the whole report to confirm that a chart in the appendix contains the only clear information about general Muslim attitudes toward the death penalty for apostasy. If I'd written the report that way I'd consider it a fault in my presentation, one worthy of correction. Plainly you disagree. I don't think we'll get beyond that disagreement.

"It's the exact number of the question you are looking for if you are seeking to find important additional information, including whether the question was asked of the general population, its exact wording, what percentages opposed, didn't know, etc."

You're describing a reference for more information, not a cue regarding specific information. I gave an example of that type of cue. The report would improve with the type of cue I mentioned.

"The discrepancy in the numbers (p. 55 vs p. 219) is obvious."

Yes, if one is looking at the numbers for a discrepancy. But that's a poor way to clarify in drill-down fashion that the Q92b was asked of the general Muslim population. It leaves the reader to wonder why, in a report on the attitudes of Muslims, the results of Q92b do not occur in the subsection on attitudes toward punishment for apostasy. Again, cues to the reader such as I mentioned earlier would have improved the report ("We focus on the section on Muslims who favor sharia ... For data on the general population of Muslims see Q92b"). Such fixes are easy.

"For some issues, in any area of research, it is necessary to contact the researchers for more information."

To paraphrase you, that's no excuse for the Pew researchers making its treatment of the apostasy issue needlessly vague. In a report on the attitudes of the general Muslim population one should be able to look at the section on the death penalty for apostasy and find information relating to the general attitude of Muslims. Anything else is an insult to the commonly understood organizational principles of expository writing.

Thank *you* for bringing this matter to my attention, by the way. Cheers.

Where is part 2?

ReplyDeletePart 2 is not complete, but here are two links to articles that will be used to support Part 2:

DeleteOverall support for hardline aspects of sharia

A method for estimating percentages of hardline fundamentalists